History: The Second & Third English Civil Wars

The Second English Civil War 1648

King Charles was imprisoned on the Isle of Wight, although he was extended the courtesy of living a comfortable life. In fact, he was handled so leniently that he was able to arrange a new treaty with the Scots. In return for royal enforcement of the Presbyterian faith north of the border, the Scots would supply Charles with an army of 30,000 men.

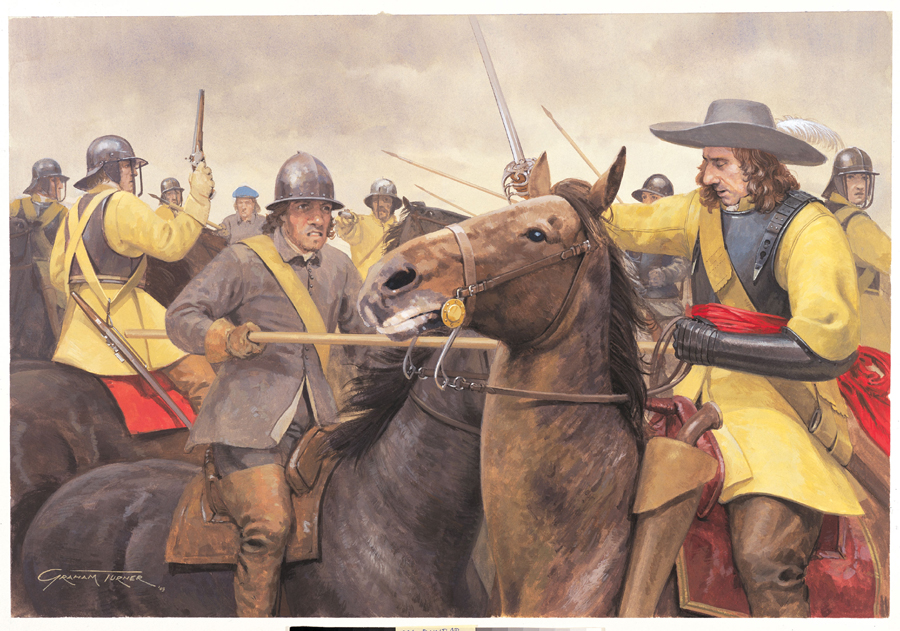

Courtesy of Osprey Publishing

This army promptly marched south, and was just as promptly routed by Cromwell at the Battle of Preston on the 28th August. That action saw the end of the Second Civil War, but now gave parliament a dilemma of what to do with a king they could not trust and who could throw the country into another war at any time. The New Model Army (but not their leader, Fairfax) wanted Charles to stand trial for his life, but there were many moderates in Parliament who thought this was a step too far. In a not so democratic move ‘Pride’s Purge’ ensured that only supporters of the New Model Army took their seats. With all opposition removed the ‘Rump’ Parliament gave itself power to pass laws without the consent of the King or the House of Lords.

It was this ‘Rump Parliament’ that put King Charles on trial and executed him for treason on the 30th January 1649. With the royal family, including the heir Prince Charles in exile, the monarchy itself was abolished. The House of Lords was disbanded and England became a republican ‘Commonwealth and Free State’. Cromwell had by this time manoeuvred himself into a position of great power and he was selected to execute a campaign in Ireland. This he did with great savagery and put down the Irish threat by commanding the massacres of Drogheda and Wexford.

The Third English Civil War 1649-1651

The execution of Charles I did not sit well with the Scottish parliament and, in a direct snub to the newly formed Commonwealth south of the border, they declared the exiled Charles II King of Great Britain and Ireland. There was a condition, however, and this was that he agreed to Presbyterian Church rule across Britain before being allowed to land in Scotland.

Charles tried to improve his bargaining position by encouraging the Royalist champion, the Earl of Montrose, to come out of exile and raise a force once more. This Montrose did, but rather than a ‘threatening’ force he invaded Scotland with a small army and tried to recruit once more amongst the Highland clans. This plan never really got off the ground and his outnumbered army was destroyed at Carbisdale in April 1650. Charles abandoned Montrose to his fate, and the brave Earl was summarily executed in Edinburgh.

Shortly after this sad act had played out, Charles signed the Solemn League and Covenant and gained the support of the Scottish parliament and their covenanter armies. Cromwell now rightly saw Charles II as the major threat to the new Commonwealth and left Ireland in the hands of his subordinates to lead an army north to confront the Scottish.

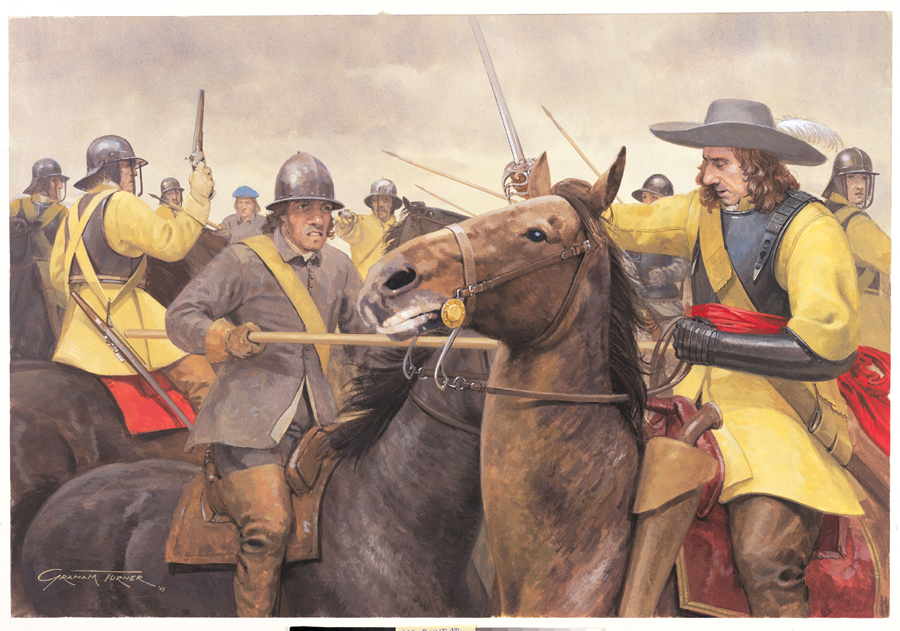

The Battle of Dunbar, courtesy of Osprey Publishing

The armies met at the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650 where the outnumbered Parliamentarian forces were victorious and Cromwell went on to occupy much of southern Scotland.

Early the following year Charles was officially crowned King of Scotland, but by this time was frustrated by the lack of unity in the Scottish Parliament and so looked south for more Royalist support. After another defeat at the hands of Cromwell’s New Model Army at Inverkeithing in July 1651, Charles marched south across the border at the head of a small Scottish force and headed to the west of England. This was a traditionally Royalist area and the hope was that many English troops would flock to his banner. The support failed to materialise in the numbers needed and Cromwell defeated Charles at the Battle of Worcester in September 1651.

Charles was forced once more into exile, spending the weeks after Worcester evading capture in disguise. Moving through different safe houses and famously hiding out in an oak tree, Charles finally made it to the coast and escaped to France. This effectively ended the English Civil Wars.

Protectorate and Restoration

Oliver Cromwell consolidated his power base after the threat from Charles was dealt with, and once again turned his attention to Ireland. In 1653 the last Confederate and Royalist forces in Ireland surrendered. By this time the country had been ravaged, and much of the Catholic land was handed over to Parliament backers and supporters.

Cromwell took on the role of Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland later that year and effectively ruled the country until his death in 1658. He was succeeded by his son, Richard, but he had no authority with the army and so abdicated in 1659. George Monck, who had been made Governor of Scotland by Cromwell during the Third Civil War, led the movement for Charles to be invited back to England and proclaimed king.

Charles II arrived back in London on the 29th May 1660, the day of his 30th birthday. The restoration of the monarchy complete, a move was made to reconcile old adversaries with the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion – Charles was not going to make the same mistakes as his father – and concessions were made to parliament.

There were notable people excluded from the act; namely the regicides who had signed the death warrant of Charles’ father. Nine were executed, others were driven into exile or removed from positions of power. Even death was not going to get in the way of the new king’s revenge; the bodies of Cromwell, Henry Ireton and John Bradshaw were exhumed and the corpses decapitated.

You might also like…

History: The First English Civil War 1642-1647

History: The First English Civil War 1642-1647 Collecting an English Civil War Army – Where to Start?

Collecting an English Civil War Army – Where to Start? Painting: English Civil War Army Uniforms

Painting: English Civil War Army Uniforms Hobby: Sir Thomas Fairfax

Hobby: Sir Thomas Fairfax Showcase: Pike & Shotte Lords of the Land

Showcase: Pike & Shotte Lords of the Land New: Pike & Shotte Armoured Pikemen!

New: Pike & Shotte Armoured Pikemen! Spotlight: Mike Jackson’s English Civil War Cavalry

Spotlight: Mike Jackson’s English Civil War Cavalry New: Pike & Shotte Herald!

New: Pike & Shotte Herald!