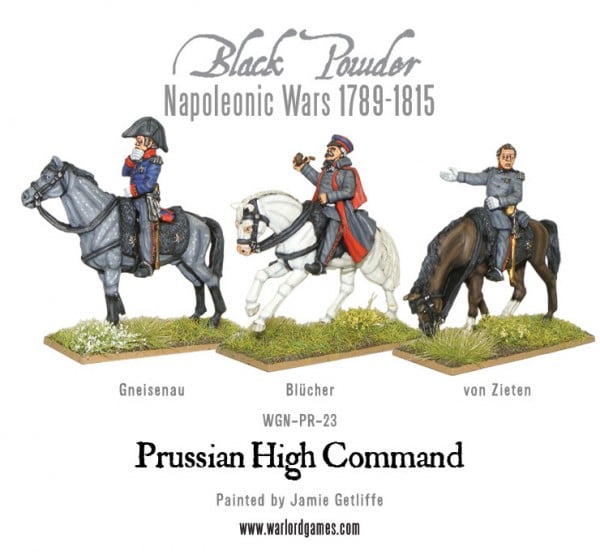

Focus: Prussian High Command

To accompany the recently released Prussian High Command – our very own David Matthews has written an article on these three famous characters of the Prussian army that sped to the aid of Wellington at Waterloo!

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher (1742-1819)

“Something could have been made of me if I only had had the sense to study”

(To his wife 1819)

Nicknamed Marshall Vorwärts (“Marshal Forwards”) by his soldiers because of his aggressive approach in warfare, Blücher, along with Paul von Hindenburg, was the highest-decorated Prussian-German soldier in history: the two are the only officers who were awarded the Star of the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross.

The peace (or in other words French occupation), after the defeats of 1806, saw Blücher leave the army due to his hatred of the French. He became governor of Pomerania, in which capacity he and Gneisenau kept the Prussian army alive. Blücher’s aggression and Gneisenau’s intelligence and subtlety were the ideal combination, forming a partnership that proved so valuable to the Prussian army.

The peace (or in other words French occupation), after the defeats of 1806, saw Blücher leave the army due to his hatred of the French. He became governor of Pomerania, in which capacity he and Gneisenau kept the Prussian army alive. Blücher’s aggression and Gneisenau’s intelligence and subtlety were the ideal combination, forming a partnership that proved so valuable to the Prussian army.

During 1807-08, an illness gripped Blücher, threatening his mental stability. He launched himself into an energetic re-fortification of Colberg, retaining his sanity for now. However this did resurface – the rigours of campaigning and mental stress of the early setbacks in 1813 and during the French invasion of Belgium in the 100 days, took their toll on the mental health of this 72 year old man.

He hated the French with venom; this passionate hatred spread to his troops and although not strategically or tactically brilliant, his force of will, passion and love of his men was enough to push the troops he commanded to throw themselves at the enemy.

It was said his remarks to his general staff on arriving above the battlefield of Waterloo, looking towards Plancenoit were simple, direct and to the point.

”Forward my children, forward, no mercy, no prisoners,

I will personally shoot any man I see with pity in him.”

1806: Auerstadt, Pomerania, Berlin, Königsberg

Blücher fought at Auerstadt, repeatedly charging at the head of the Prussian cavalry, but too early and without success. In the retreat of the broken armies he commanded the rearguard of the army.

1813: Lützen, Bautzen, Katzbach, Mockern, Leipzig

At the Battle of Lubeck his force was defeated by two French corps on 6 November. The next day, trapped against the Danish frontier by 40,000 French troops, he was compelled to surrender with 7,800 soldiers at Ratekau and was soon exchanged for future Marshal Victor, duc de Belluno. He was present at Lützen and Bautzen. When the war was resumed, he became commander-in-chief of the Army of Silesia, with August von Gneisenau and Karl von Muffling as his principal staff officers and 40,000 Prussians and 50,000 Russians under his command. A vision of the future to come. He defeated Marshal MacDonald at the Katzbach, and by his victory over Marshal Marmont at Mocker led the way to the decisive defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig. This was the fourth battle between Napoleon and Blücher, and the first that Blücher had won. Leipzig was taken by Blücher’s own army on the evening of the last day of the battle.

1814: Brienne, La Rothiere, Champaubert, Vauchamps, Château-Thierry, Montmirail, Laon, Montmartre

1815: Lower Rhine (Battle of Ligny), Battle of Waterloo

General August von Gneisenau, (1760-1831) – Blucher’s chief of staff.

Born in Saxony, his father an impoverished Austrian noble and a Saxon artillery officer. It is reputed that Gneisenau was born on the retreat from Torgau. Gneisenau served in the Austrian cavalry, a hussar much like his future commander, Blucher. He went to Canada in 1782 in an Ansbach light infantry unit hired by the British but saw no active service. Transferred to the Prussian army he was a company commander in 1806. In 1807 he transferred to the general staff and played a considerable part in the reformation of the Prussian army after the embarrassments of Eylau and Friedland. In 1809 Prussia refused aid to Austria, Gneisenau resigned in protest. As the 1809 campaign was a near run thing, this aid would have been invaluable.

However he was employed on secret missions to England and Russia, and joined Blüchers staff in 1813 for the Leipzig campaigns – he was raised to Chief of Staff after Scharnhorst’s death that same year, a position he retained until his political views pushed him into obscurity after Waterloo.

Wilful, intelligent, and broad-minded, he complimented Blücher in a relationship that was more correct than friendly. He was credited with planning Blücher’s strategy, but in reality this may have consisted of issuing the orders to implement Blücher’s vociferous (and often venomous to the French), inspired decisions.

He always wanted an independent command – but unlike Blücher did not have the charismatic ability to inspire men that his compatriot possessed. Energetic and courageous, when Blücher returned to the army after Ligny, Gneisenau had set the entire force remaining on a retreat to Namur, thus condemning Wellington to defeat. Only because of his respect for his commander, did he consent to the request of Blücher to send two corps towards Wavre and on to Waterloo. Although greatly improving the Prussian staff system, modern strategists and tacticians would be horrified at his staff decisions during the campaign.

Gneisenau died in 1828 of cholera – a Field Marshall in the Prussian army, a patriot and champion of Germanic unity to the end.

Hans Ernst Karl Graf von Zieten (1770 – 1848)

Prussian Hussar officer and Field Marshal, Graf von Zieten served as a General of Hussars and as the commander of the Upper Silesian Cavalry Brigade under Field Marshal von Blücher.

Graf von Zieten’s chief fame rests with his actions in the 1815 campaign. Although he held a brigade command in 1813, including the Leipzig campaign, it was as a lieutenant general in command of I Corps in 1815 that he was most prominent. His corps fought a holding action against the French on 15 June, and was heavily engaged against the French the next day at the Battle of Ligny, and then again two days later on June 18 during the march to Mont St-Jean and at the Battle of Waterloo as troops under his charge shored up Wellington’s left flank late in the day in cooperation with Bulow’s 4th corps.

General von Zieten later commanded the Prussian forces during the occupation of France. On 1 July, Zieten’s I Corps participated in the Battle of Issy just outside the walls of Paris. At the end of the campaign on 7 July, his corps was granted the honour of being the first major Coalition force to enter Paris. He attained the rank of field marshal in 1839. He died in May of 1848 in Bad Warmbrunn.

Fielding Prussian senior officers in Black Powder

Some suggested rules for fielding the Prussian High Command in games of Black Powder:

Blücher

• Has a command rating of 8.

• He is Aggressive (page 95 of Black Powder).

• Blücher adds two attacks to any combat that he is involved in.

• He has the special rule ‘Marshall Vorwärts’ (Marshal Forwards). When fighting against the French with Blücher in command, Prussian units can make a normal move before the game begins, and in addition one unit in the army may be given the Ferocious Charge special rule.

Gneisenau

• Command rating of 8

• He is cautious, methodical, use the High Decisiveness rule from page 95 of Black Powder.

• If the line is broken by the adversary, on a roll of 1, 3, or 5 the army withdraws.

• If partnered with Blücher, a joint command rating of 9 is awarded.

Zieten

An unassuming officer, I would recommend using a bonus to bring on reinforcements if he is in command with a rating of 8.

Bibliography and references.

A military atlas of the Napoleonic wars, J.Esposito & John R Elting.

Napoleonic handbook, Partridge & Oliver.

You might also like…

History: Field Marshal Prince Gebhard von Blücher (1742-1819)

History: Field Marshal Prince Gebhard von Blücher (1742-1819) History: The 100 Days Campaign

History: The 100 Days Campaign Preview: Prussian High Command – Blucher, Gneisenau and von Zeiten

Preview: Prussian High Command – Blucher, Gneisenau and von Zeiten New: Napoleonic Prussian High Command and Jagers

New: Napoleonic Prussian High Command and Jagers History: Napoleonic Artillery of the Peninsular War, by David Matthews

History: Napoleonic Artillery of the Peninsular War, by David Matthews History: The Battle of Waterloo – part 5

History: The Battle of Waterloo – part 5 History: Sir Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington (1769- 1852)

History: Sir Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington (1769- 1852) Napoleon’s Eyes and Ears – The Chasseurs à Cheval of the French Army

Napoleon’s Eyes and Ears – The Chasseurs à Cheval of the French Army