Miniatures and resin casting processes

Some exciting things are happening here at Mantic HQ. We recently cleared out a spare room* and fitted it with numerous pieces of equipment and chemicals marked with warning signs, so that the area resembles a mad scientist’s lair. That’s right; Mantic is officially casting resin in-house for the first time!

So, why resin? We already cast our metal models in house, which covers a lot of our ranges. There’s plastic for a lot of other products too, which is outsourced. Although we have released resin models in the past (the Greater Earth Elemental and Abyssal Fiend, for example), this has normally been in much smaller numbers that what we’re planning for future and was also outsourced.

When we decide to create a new model, the material used to make it is based on a few different parameters. Plastic models, while cheap to produce and popular with the community, are initially expensive because of the tooling cost to actually create them. This means they have to sell in large numbers to cover that initial cost, so only models that will be used in large numbers – like core troops for armies – are the best for this method.

PVC (which covers restic, too) is a bit less costly than plastic, but limited in terms of the size of the kit (the number of components) and what can be achieved in the model, such as the pose and the physical size of the model. Metal, meanwhile, has a low initial cost and although it is more expensive per set, it is very economical as almost all waste materials can be recycled and used again, as well as the ability to easily cast models on demand. Metal does add a considerable weight to products, however.

Resin is, like metal, more expensive per set than plastic, but it is also wasteful. The advantages with resin are that it can hold fine detail better than other materials and also handle complicated shapes that would not be possible in the other materials. Finally, it allows us to create large models with less consideration for weight than metal and far less expensive tooling than plastic.

So, to take the new Thuul as an example. These were originally pitched in metal (our metal is spin-cast, by the way), but as we started to cast the sub masters (which you’ll hear about later) in metal, they weren’t forming correctly. The issue was that the tentacles on the models were not being filled when the metal went into the mould, so they weren’t casting. Although such things can normally be corrected, in this case, the models were too complex for the material.

Resin, on the other hand uses a vacuum chamber to draw the material out to the edges. This, in addition to a more pliable mould, means that we can cast the tentacles perfectly with few, if any, errors. The miscasts are separated, so the models going out to be sold will have all of their tentacles intact – what more could anyone wish for?

We get a lot of questions about the processes used to create our models, so we thought it would be a good opportunity to show what is involved in taking a sculpt and turning it into a mass-produced resin model.

It starts with the master models. These are, at the moment, all 3D prints of digital sculpts, cut into components based on advice from the casters and studio. You can also use traditionally sculpted models and even other resin models as masters, you just need to be careful and ensure that the detail is strong enough.

Ricky, our resident Casting Wizard** goes over the masters and looks for areas that will need help to form. Areas that go in the opposite direction of the main feed (where the resin will be poured in) will need a feed of their own, while areas that extend out a long way will need a vent. It’s more complicated than this, but the basic thing to remember is that feeds and vents ensure that the resin goes where it is needed. Ricky cuts and glues small lengths of plasticard to the models to create these, as they will form as pipes when the mould is created. The main feed is made of thick plasticard and wax, placed usually under the model – so when it is cast, it is upside-down – gravity helping the model to form.

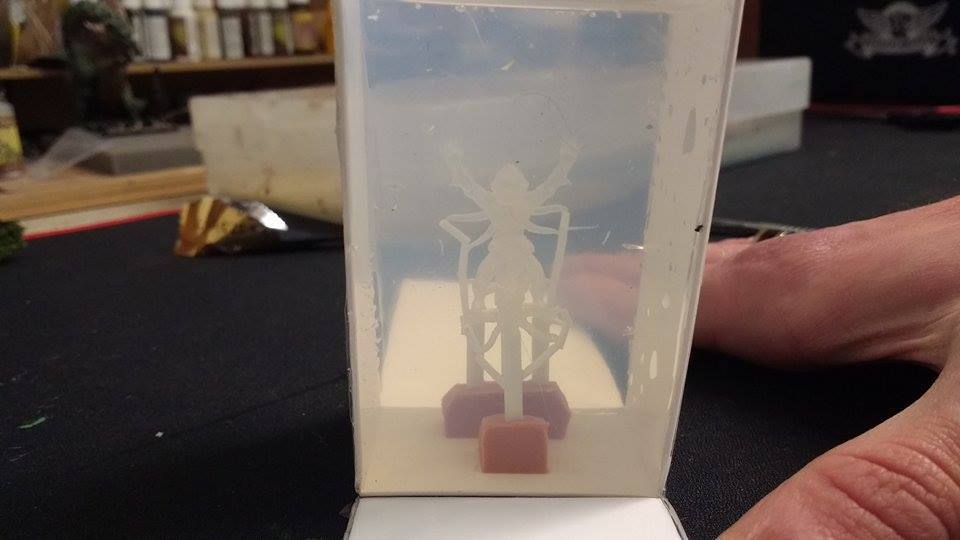

Once the master is ready, it is placed into a container, which is then filled with silicon. This will create the mould around the model. Silicon moulds have a relatively short lifespan, but their flexibility allows for more complex models. The vacuum chamber is used to draw out any air bubbles from the silicon, then it is left to set for a day or two. After this, it will be removed from the container and cut about two thirds of the way through, so the the mould can be opened and the master removed.

The resin itself is a two-part mix, that casts quickly and is sealed in the vacuum chamber to draw out excess air and bubbles. Ricky has been overseeing the entire process, as somewhat of a veteran of resin casting. The process itself is dangerous, so safety equipment is worn and the room is ventilated.

Although the new mould can be used to cast resin, it will only cast one model at a time, which isn’t going to cut it for global distribution. So, in order to get the numbers we need, we use this mold to create a number of models called sub-masters. These are as close to the original as the material allows and will be used, exactly as above, to create a single mould with multiple models inside. Congratulations, we have made it to the production mould! This is where your Thuul will come from.

At the time of writing the first resin models have already left the building as part of the Trident Realm release. We plan on making even more, such as the ‘Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Moe’ Diorama for The Walking Dead: All Out War. Ronnie’s excited because this means we can make really big models for other games, such as, say, a Tree Herder for Kings of War?

We’ll also be looking at the models we currently produce and working out what material would be best for these. These are complicated decisions, made on a case by case basis and while we will convert some metal models over, most of the range will likely remain as it is now***. We are also looking into bringing back some of the older resin models that are currently out of production, such as the Marauder Stuntbot and Urban Pattern Ancestor for Deadzone.

In short, we’re now capable of producing models that we wouldn’t have been able to make before and this opens up a world of possibilities for our games. We hope you enjoy your new resin miniatures and look forward to making many more in the future!

*spare being that no one was sitting in it at the time. It’s like musical chairs here, sometimes.

**this is what happens when you let someone choose their job title. We’re lucky it wasn’t Casty McCastFace.

***equally, this means that we can’t say right now which models will be changing. It’ll be worked out when the metal molds wear out.

The post Miniatures and resin casting processes appeared first on Mantic Blog.